In England, many European countries and in America, motorcycle engine-powered three and four wheeled vehicles had a period of promoted popularity. In some places three-wheeler road tax was less than for four wheeled vehicles and that economy drove sales. But in a time when horse and buggy transportation was still strong, cycle cars with three and four wheels were also minimalist transportation, a first step into mechanized transportation. Even the four wheeled versions were lightweight, mostly narrow track machines with tandem rather than side by side seating.

Though starting around 1909, by 1914 cycle car popularity had peaked then soon declined, likely due to the advent of Henry Ford’s very affordable Model T. By this time about 75 American cycle car manufacturers advertised their product. Using sourced drive line components and fabricating other pieces as needed, they were not always very sophisticated or mechanically sound.

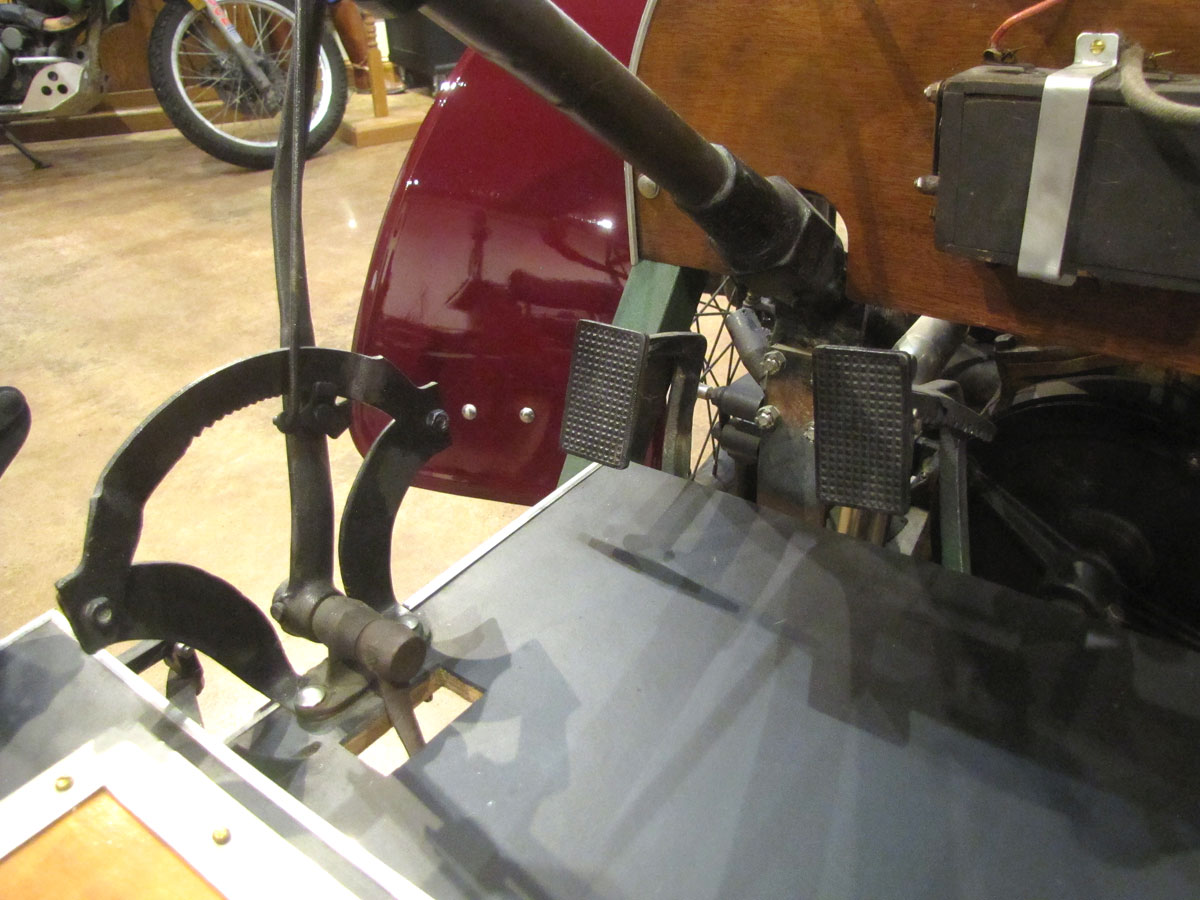

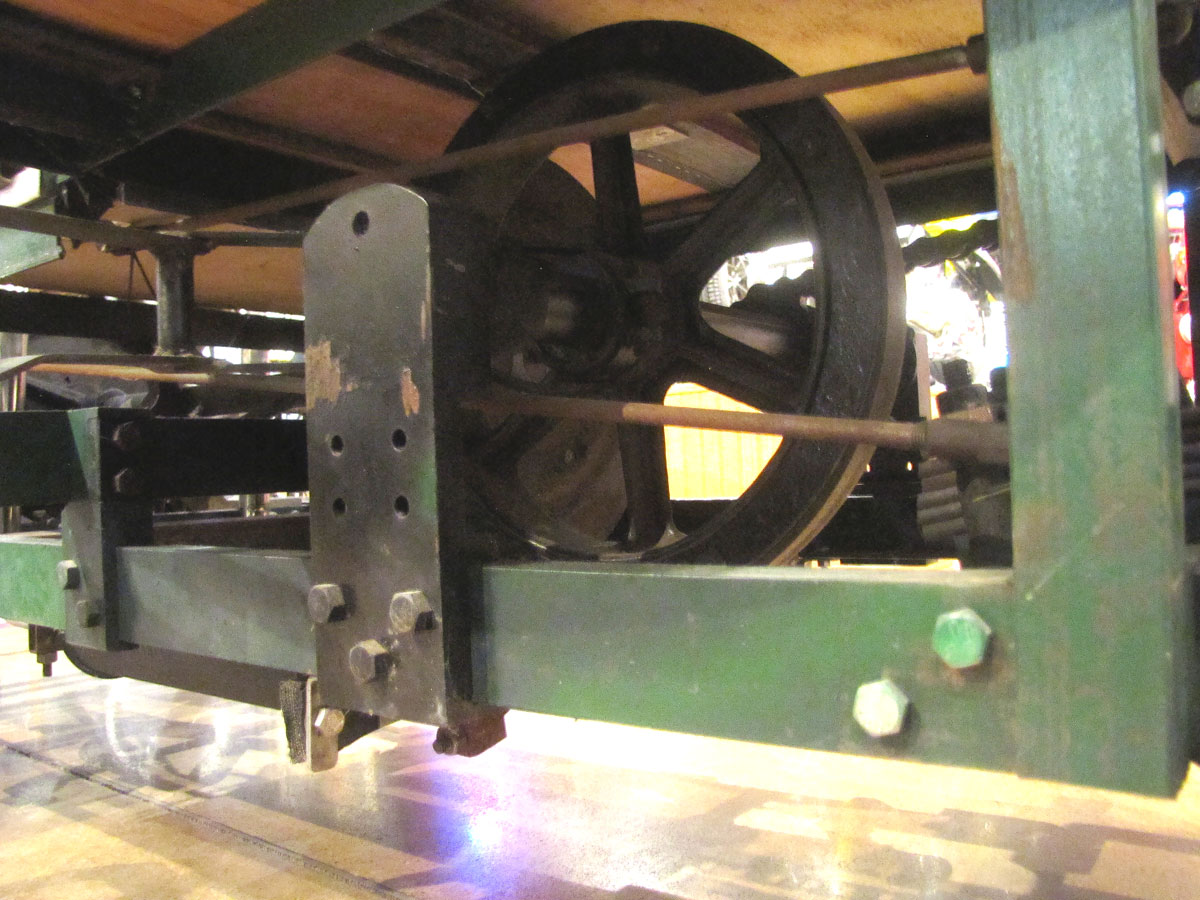

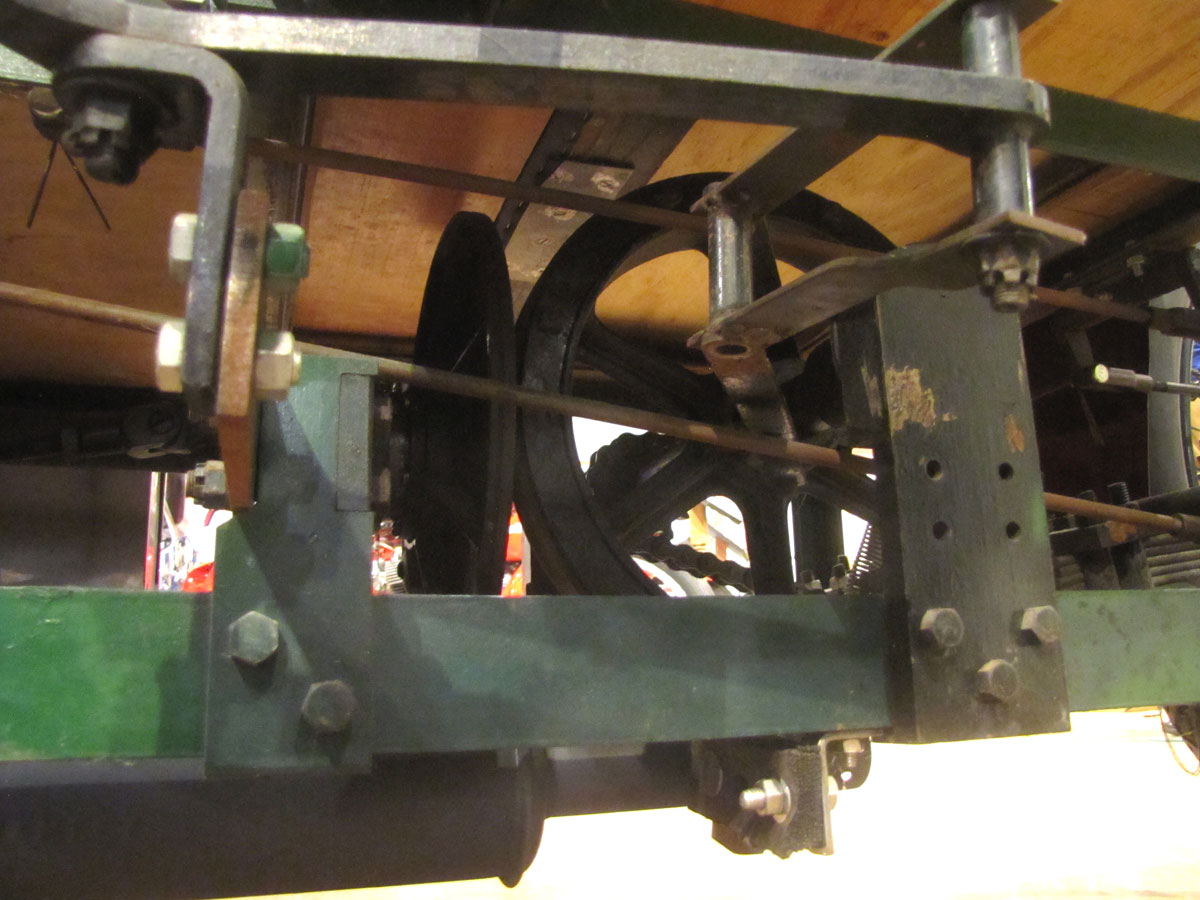

Looking at this machine, the tall lever to the left of the driver’s seat changes the drive ratio of what we might call a “planetary transmission” system. A friction disk wheel runs at right angles to the external flywheel on the engine. As the friction wheel is moved across the flywheel, the drive ratio changes, even moves to reverse; an early version of the CVT used by today’s auto makers. This system was also employed by makers of machine tools like drill presses.

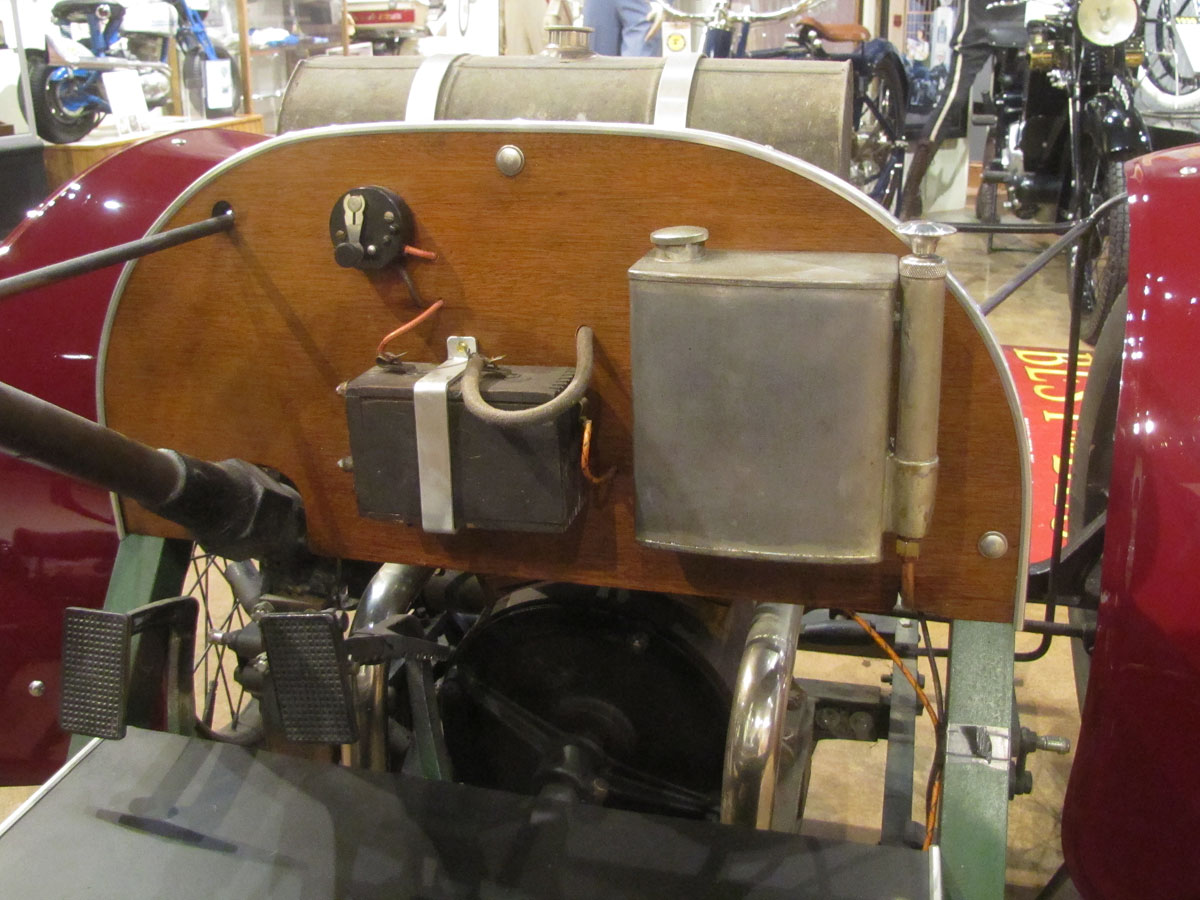

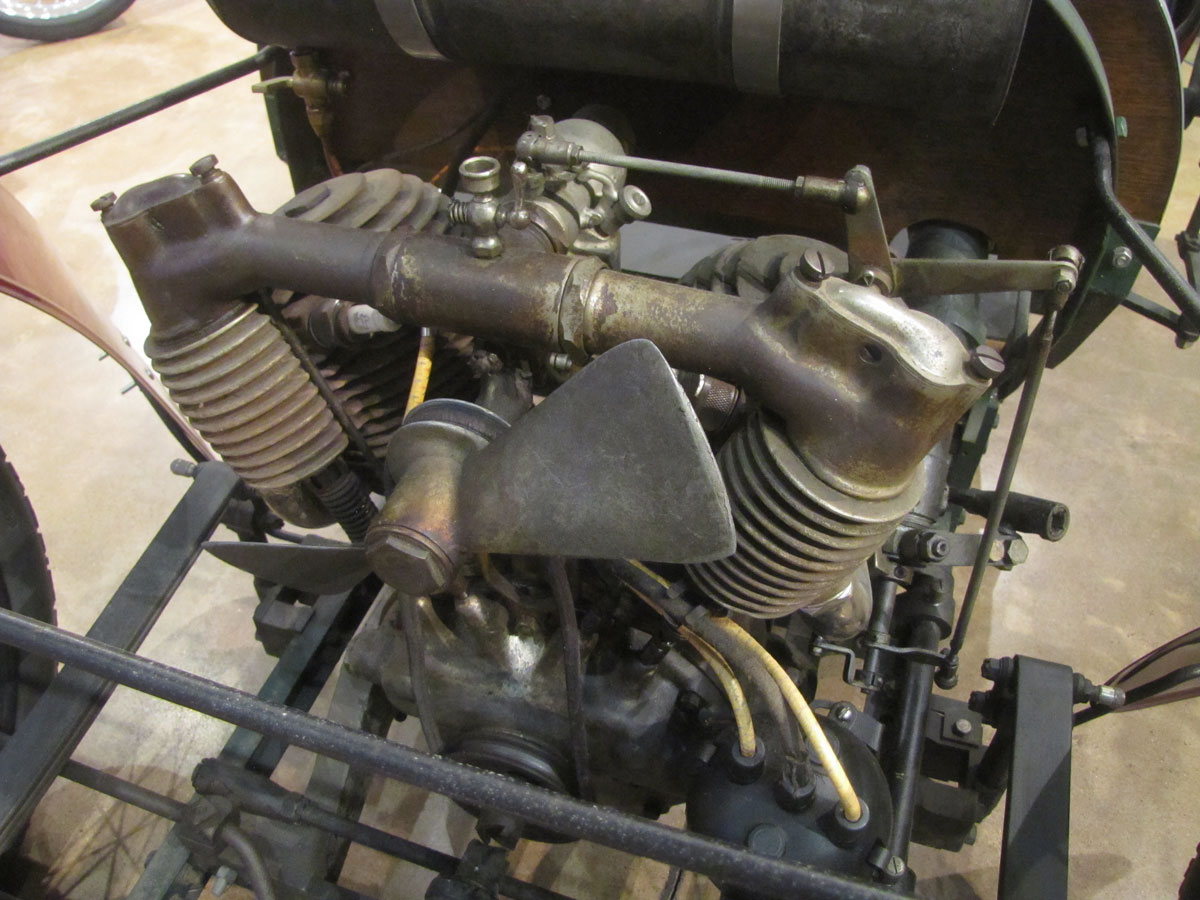

Operation of this Spacke cycle car called for both hands and both feet. The ignition is battery and coil through a distributor with the switch on the dashboard. One lever on the steering wheel sets the throttle, the other the spark advance. Battery and oil tank are on the dash, fuel tank behind the engine, gravity feeding the carburetor.

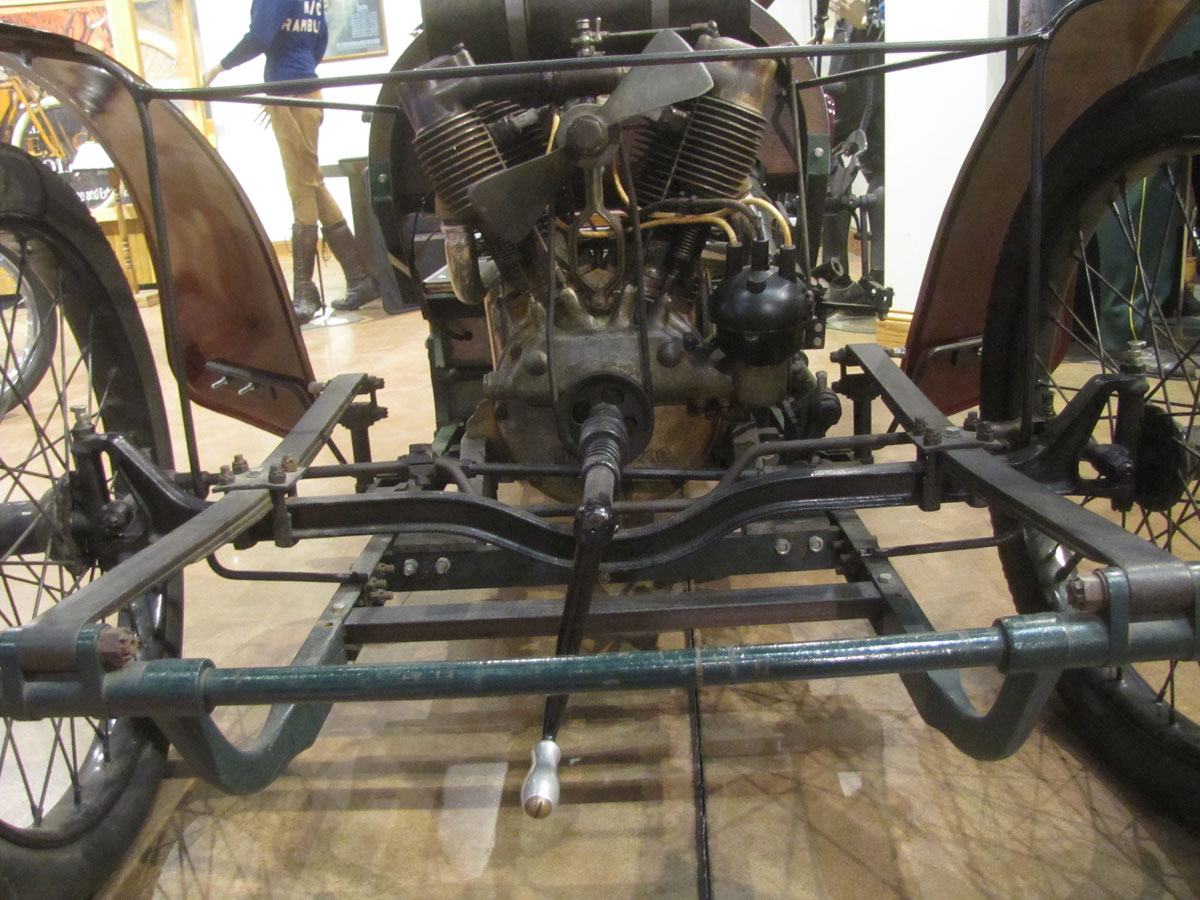

As you can see the open, fan cooled engine is started by a hand crank down low in front. The left pedal is the rear wheel brake, the right pedal engages the transmission. The other tall lever, a bit forward of the transmission speed selector, is a hand brake/parking brake. (A version of this engine powers the Sears DeLuxe Dreadnaught Twin displayed in the Early American Transportation INNOVATION exhibition.)

While many cycle cars including the Steco and Merz here at the Museum used belt final drive, this machine employs a massive, for about 9 horsepower, sprockets and drive chain. Rear suspension is by swingarm controlled by dual leaf springs. The front axle is a handsome casting again hung on a pair of leaf springs. Steering is pretty typical with a tie rod and drag link. Frame rails are channels with cast lugs on each end to accept suspension components.

The cycle car, being of light construction and low to the road worked well in urban settings. But in this era most rural roads were rough and rutted. Cars and horse drawn conveyances had about a 56 inch track, but cycle cars at about 36 inches had a tough time of it.

This Spacke Cycle Car from the Jill & John Parham Collection is displayed in the Hagerty Motorcycle Insurance Best of the Best Gallery. When you visit the National Motorcycle Museum you can look at it in detail, but also view the four-wheeled Merz and STECO cycle cars displayed in the Early American Transportation INNOVATION exhibit area.

Specifications:

-

- Engine: Air-Cooled V-Twin

- Type: Inlet Over Exhaust

- Displacement: 70.62 Cubic Inches

- Horsepower: 9HP, Rated

- Bore & Stroke: 3.50” x 3.67”

- Carburetor: Schebler

- Ignition: Battery, Distributor

- Transmission: Planetary

- Final Drive: Chain

- Starting: Hand Crank

- Brake: Band and Internal Expanding, Rear

- Wheels: 3.00 x 28 Inches

- Suspension: Leaf Springs

- Frame: Steel Channel, Cast Lugs

- Wheelbase: 68 Inches

- Track: 42

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Cool, thank you.