French and Italian racing car engineers were experimenting with shaft driven overhead cam engines by 1909. But in that era motorcycle engineers were satisfied with inlet over exhaust (IOE) designs and side-valve engines were just coming into being. Reading Standard was one of the first American makers to move to a true “flathead” design where cams opened intake and exhaust valves. Engine speeds were low and one intake, one exhaust valve per cylinder were adequate. But as horsepower wars started during the board track racing era, induction and exhaust had to be improved and four valve heads, with all valves operated by pushrods, became the norm on motorcycle racing engines.

Looking at patents from other engineers and studying the competition in America and Europe, ideas were exchanged. Within the bounds of need and budget, higher tech designs were tested. From about 1905 to 1910, there was a lot more horsepower being made and speeds being attained than the flimsy early race tires could support. Reading most period accounts, like those in Don Emde’s SPEED KINGS book (click here to get one), tread separation and tires coming off the rim accounted for about half the racing crashes, and they were too often fatal. Nonetheless, engineers like Andrew Strand took a great leap in giving his Cyclone engine the very best of current technology.

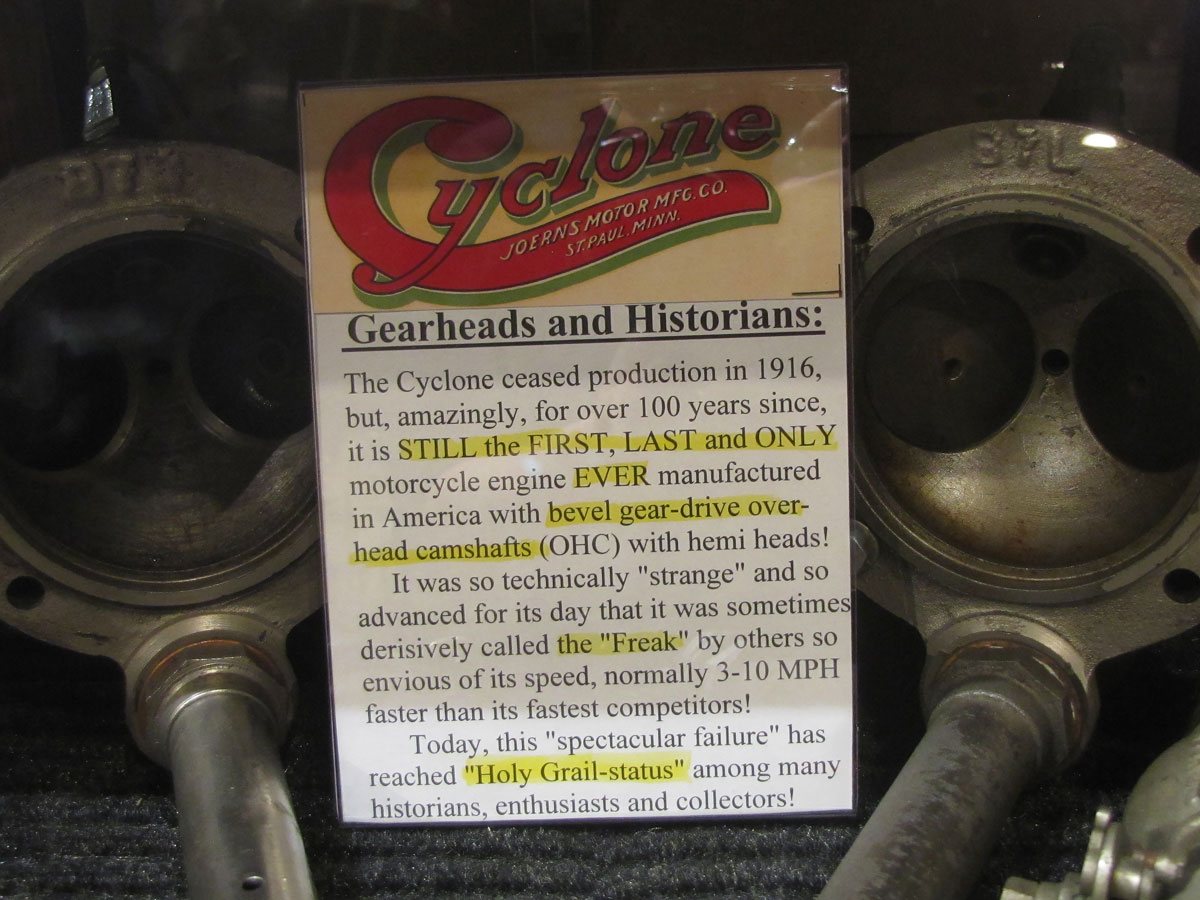

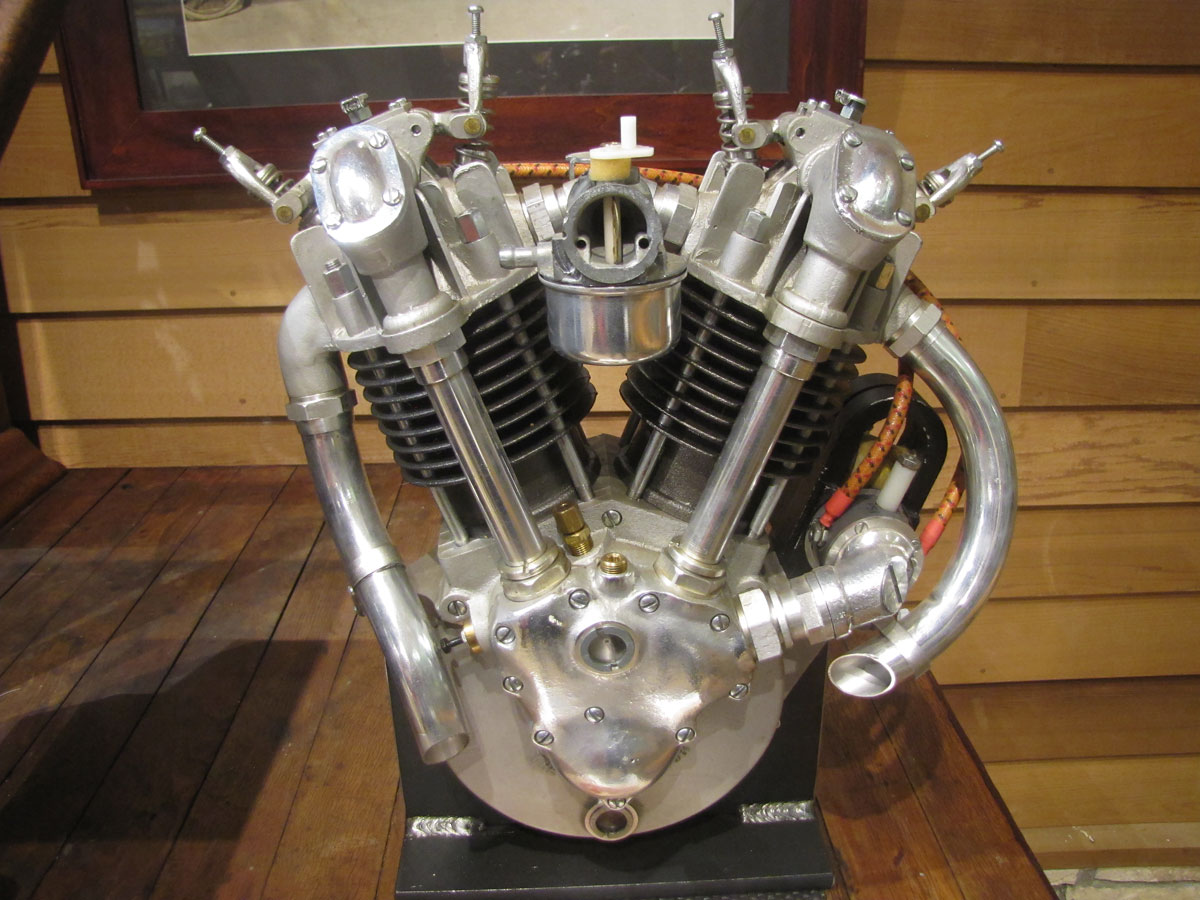

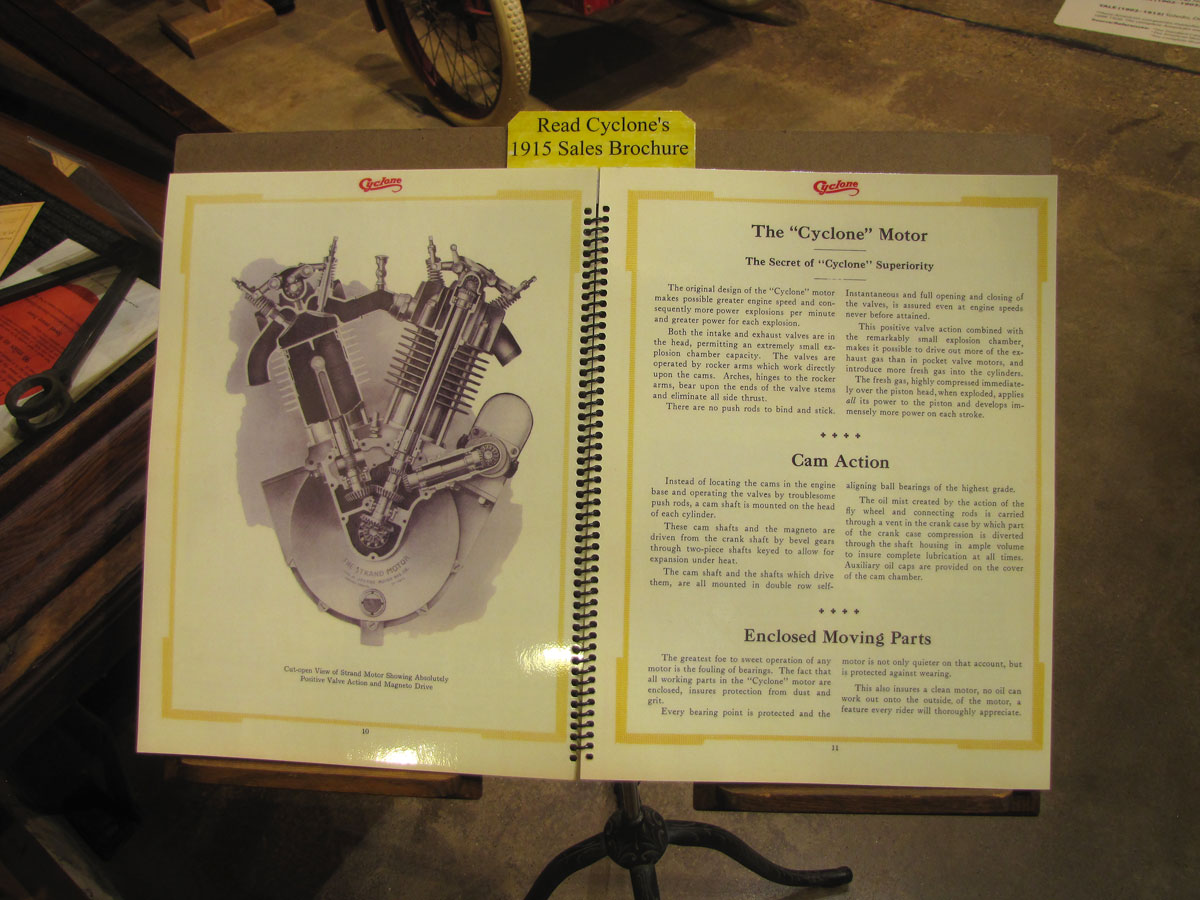

Though his official job title was “Shop Superintendent,” Andrew Strand had done engineering work for Thiem Mfg. Co, eventually to become Joerns Manufacturing Co. of Minneapolis. But Strand didn’t have Gilmer belts to drive the inlet and exhaust cams like millions of cars on the road today; the necessary polymers and fibers had not been invented. A roller chain may have worked, certainly a bank of gears to move the rotation of the crankshaft up to the cams like Honda used in its grand prix engines in the late 1950’s. Instead Strand went the way Ducati and Norton went decades later; as you can see in the photo, he used bevel gears and shafts to drive the camshafts, a bevel geared shaft on ball bearings going to each cylinder head.

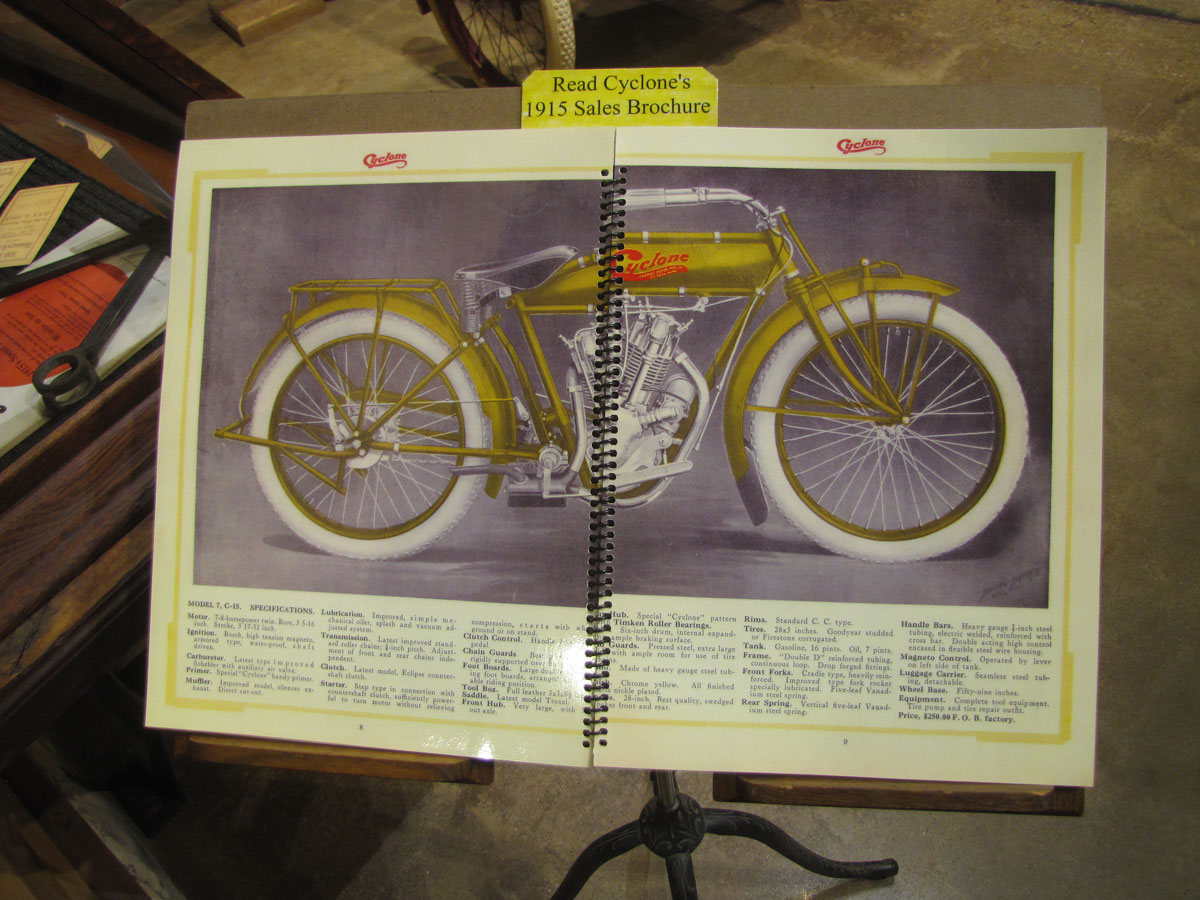

The chassis of the road going version of the Cyclone the pictured engine components came from incorporated an interesting rear suspension; a vertical leaf spring between the rear wheel and frame seat post area controlled a swingarm suspension. This was not used on the racing frame and Bob Chantland, lender of these parts and extreme researcher on the Cyclone motorcycle notes a “stripped stock” model appeared in the catalog for 1915, not directly described as a racer. Early Cyclones were built for the track and later on stripped street Cyclones sans the rear suspension were tuned and raced.

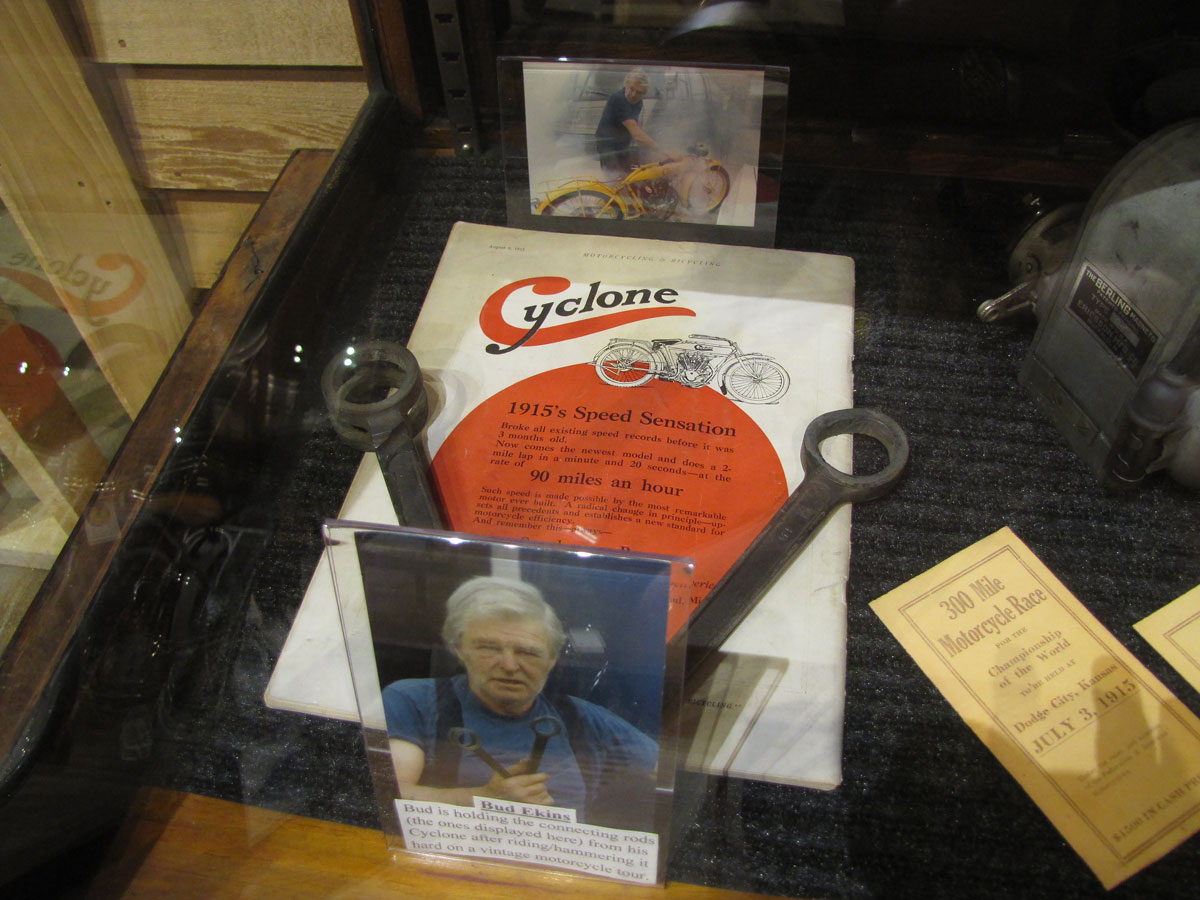

Racing development is tough business as witnessed in the mid-1990’s with the Harley-Davidson VR1000 road racing program. On track, most of the Cyclone’s racing failures were not occurring in the valve train, even the engine, but rather basic stuff was breaking; fuel tanks ruptured, fuel lines cracked, spark plugs fouled and of course, tires blew. But the Cyclone showed well and even won races. Don Johns was hired to race the Cyclone and the company got national attention when Johns won the big race in Stockton, California in September, 1914. In the 1915 grueling 300 mile Dodge City Race, Johns had lapped the field in the first few two-mile laps, then the demons struck shortly before going 100 miles. Time and lack of capital were the biggest obstacles to advancement of the Cyclone’s superior initial design. R&D being perfectly normal in most instances, but the time and the money ran out in the midst of other negative influences occurring in transportation-related markets and the escalation of world war, etc. Added to all that was the quite obvious fact that this fabulous, low-production engine was extremely expensive and time-consuming to manufacture and could not possibly be made at a competitive price.

Mechanically speaking, there is no more exciting ’teens motorcycle to observe than the Cyclone. Bob Chantland loaned to the National Motorcycle Museum the key parts of the Cyclone valve train; the “gearbox” drive from the crankshaft, the shafts, the gears and the cylinder heads. If you ever did get next to a gorgeous yellow Cyclone at a California concours or while walking The Art of the Motorcycle by the Guggenheim Museum 20 years ago, you would not be privileged to peer inside one of these super rare bikes. But here at the National Motorcycle Museum, laid bare thanks to Chantland, are the key components, Strand’s design and engineering arriving decades early in the motorcycle industry.

Yes, much like Pierce motorcycles, Cyclones were very expensive to build. Engineered as race bikes converted for “street” use, few riders could afford one, and few were made. And like dozens of motorcycle companies from 1900 to The Depression, finances played a big role in success or failure. Joerns was under-capitalized, the motorcycle could have been better marketed and track failures even when Don Johns was at the controls did not boost the corporate image as it did for Indian. Given all sources of information, it appears less than 300 Cyclones were made, and Bob Chantland’s is #4, probably made in early 1915. The cylinder heads are part of the Early American Transportation INNOVATION exhibition currently at the National Motorcycle Museum, now reopened and awaiting your visit. By the way, if anyone has any Cyclone-related information or memorabilia, etc. to share, it would be appreciated if they could contact the museum.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

WOW thanks Bob for showing this fabulous engine and Bike It would be nice to see you and the Cyclone at the Museum if they conquer the Virus. Maybe next year the Vintage Rally will take place.

if you love this machine, you were born at the wrong time like me